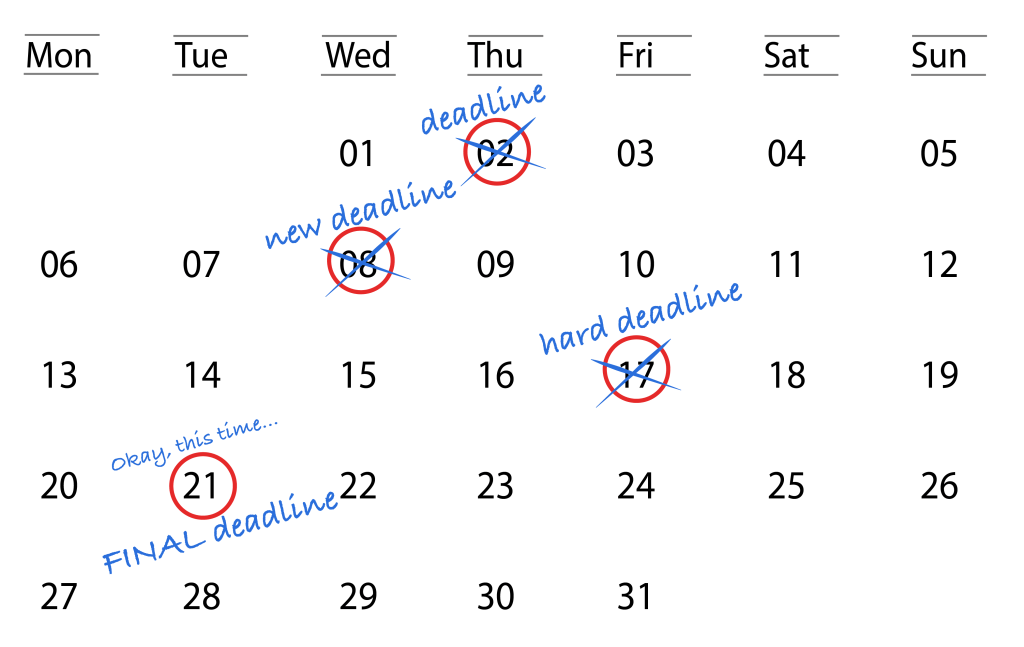

The last time my supervisor asked me when he could expect me to write up a report of our project, I had confidently said, “two weeks.” It has been two months since and I’m now two weeks away from completing it. I think.

The idea of us being terrible planners because of our biases – planning fallacy, has been around for almost 50 years now. The term was first popularized by Kahneman and Tversky in 19791, and since then there has been a number of studies that have tried to understand where this bias to underestimate the time comes from. Explanations ranging from “we want to be optimistic and hopeful about the future” – optimism bias (consequently don’t take into account the delays that are not under our control), to “we just forget how much time it has taken for us to do a similar task in the past” have all been suggested and tested.

Roger Buehler and colleagues conducted a study2 in which they asked a bunch of students to estimate how much time they’d need to complete their honor’s thesis. The students estimated 33.9 days. They were then asked for an optimistic guess and a pessimistic guess, to which the students answered 27.4 days and 48.6 days, respectively. The actual number of days that they took was 55.5 days . If you’re thinking perhaps these students were taking an honor’s course for the first time, you’ll be disappointed to hear results of the next experiment3, because researchers then asked students to predict how much time it’d take for them to complete non-academic tasks (“fix my bike”, “clean my apartment”, “write a letter to a friend”, and alike). While the average prediction was 5.0 days, actual time they took to complete the task were 9.2 days! Clearly, we’re not immune to planning fallacy outside of academia either.

image idea credit: Annelies van Nuland

It’s not just that we’re simply bad at predicting the required time, but particularly bad at taking our previous experiences into account when planning for the future.

Not convinced yet?

The Sydney Opera House (that lotus-like structure you’ve seen in every picture of Sydney, Australia), was supposed to be completed in 1963 for \$7 million. Construction had started in 1959. It was finally completed in 1973, for 1,357% over budget of \$102 million4!

(this is when you take a walk and let this whole planning fallacy thing sink in)

What now?

There is hope. You can become better at making time estimates, if you do these two things:

- keep yourself continuously monitored;

- friends for advice.

It is good to think of similar jobs you’ve done before. Then you can make a better planning of the new task. And you can, keeping your eye on progress, your timeline adapt continuously, so you actually get your deadlines. And now the part ‘friends’. According to research, you can bypass the optimism bias if you like other people’s progress closely. So ask before you start a new job, a friend to estimate how long it will cost you. If you feel that they are unreasonable and too pessimistic, wait complaining, start with the first part of your job and you will soon find that they were right.

Well … where is that report that I had to write?

Further reading

Planning fallacy – wikipedia

Optimism bias – wikipedia

Evidence-based scheduling – blogpost

This post on planning fallacy was written for the Donders Wonders blog and the final version that got published there can be found at – this link. You just read the version that I first started out with. Basically my second draft.

-

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures. TIMS Studies in Management Science, 12, 313–327. ↩︎

-

Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Ross, M. (1994) Exploring the “planning fallacy”: Why people underestimate their task completion times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 67(3), 366-381. ↩︎

-

Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Ross, M. (1995) It’s About Time: Optimistic Predictions in Work and Love, European Review of Social Psychology, 6(1), 1-32. ↩︎

-

See Wikipedia page of Sydney Opera House, completion and cost section – link ↩︎