If you’re in the field of social sciences, there is no way you haven’t heard about the replication crisis in one form or the other. There are studies that paint quite a grim picture, then there are studies that provide some consolation and say that the numbers are slightly better than what other papers say. In either case, the conclusion is that something has to change in the way we think about doing science.

In their article titled Heating up the measurement debate Laura Bringmann and Markus Eronen argue that physicists and the ways in which physics experiments are carried out, in general, can provide us with some useful tips regarding how to proceed from here. They begin by drawing parallels between the two fields by using the example of understanding temperature as a concept, contrasting it with advances in measuring temperature using a thermometer. They highlight the milestones achieved in the understanding of the theory by narrating incidents such as Johann Georg Gmelin’s visit to Siberia, where his mercury thermometer measured a temperature of -84.4 deg.C! But only decades later it was discovered that mercury’s freezing point is -38.83 deg.C, proving that the understanding of what temperature was as a concept was limited. They then make their case for advancing theory and not only the measuring devices with the example Regnault, who made gas thermometers that had a record high precision of 0.01%, but this breakthrough added very little to the concept of heat or temperature when compared to Joseph Black’s contribution - the theory of latent heat. Without going into details, it suffices to say that technological advancement seldom directly aids to the understanding of a concept. But developing a good theory does. In the field of neuroscience, I think, development of theories have not kept up with the rapid development of imaging methods.

How can we come up with good theories?

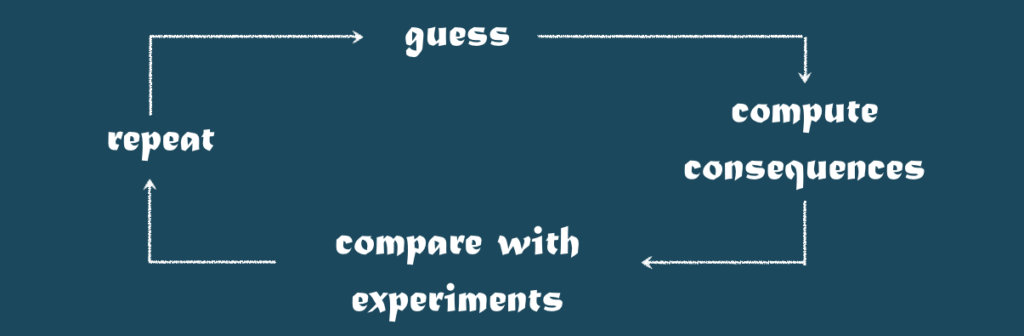

Here, I turn to one of my academic idols, Richard Feynman. In one of his lectures he explains how one can come up with new laws. The process he says, is as follows -

- first guess it

- then compute the consequences

- compare with experience or experiment

- if it disagrees with the results, take another guess

He then continues to say one of the imperative facts that in my opinion, every researcher should keep in mind.

It doesn’t make a difference how beautiful your guess it. It doesn’t make a difference how smart you are who made the guess, or what his name is. If it disagrees with experiments, it’s wrong. That’s all there is to it.

- Richard Feynman, on scientific method

But psychology is not the same as physics, you might say. Variables of an experiment in physics are often known and controllable whereas, human and animal behavior has all these hidden attributes. We can talk about wants, (and) needs, and intentions behind actions when it comes to observing behavior. Physicists have at least figured out how many types of forces are there in the universe. Where do we start? Apart from a handful of good theories (like reinforcement learning, models for neuronal firing, memory…) we are far from being able to make air-tight predictions about an outcome of a study. I absolutely agree. It’s not straight-forward. There is much work to be done.

What could a good researcher possibly do?

Laura and Markus discuss a few things in their paper:

- think about mechanisms

- are there alternative explanations to the observed behavior?

- how is the behavior operationalized?

- make it a robust finding by working on the theoretical predictions

These suggestions are great. To add to that, I’d like to conclude by pointing out what Feynman says about sticky situations when you have guesses A and B, in very different forms, that sound very different, and have different philosophies, but both agree with the experiments. If they both agree with experiments, there is no way of knowing which one is right. This, crucially, is where psychology (and neuroscience) stand at the moment, I think. And all that a good researcher can do is to keep both theories in mind, and use the one that let’s them make better prediction given the context. Feynman uses examples to explain why thinking about differences in philosophies and allowing for them to exist is important in this video.

I only mean to ask you to keep an open mind and develop theories that can make precise predictions. Now, enjoy Feynman.

PS: Thank you for your time. Feel free to reach out, if something popped up in your head when reading this post.